Why are there 12 Notes in Western Music 🌱

The justly tuned pitch ratio of a perfect fifth is 3:2 (also known, in early music theory, as a hemiola),[10][11] meaning that the upper note makes three vibrations in the same amount of time that the lower note makes two.

Sound is produced when an object vibrates, creating a pressure wave. This pressure wave causes particles in the surrounding medium (air, water, or solid) to have vibrational motion. As the particles vibrate, they move nearby particles, transmitting the sound further through the medium. The human ear detects sound waves when vibrating air particles vibrate small parts within the ear. As a sound wave moves through a medium, each particle of the medium vibrates at the same frequency. This is sensible since each particle vibrates due to the motion of its nearest neighbor. A guitar string vibrating at 500 Hz will set the air particles in the room vibrating at the same frequency of 500 Hz, which carries a sound signal to the ear of a listener, which is detected as a 500 Hz sound wave.

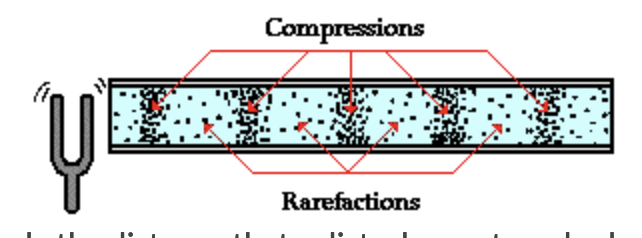

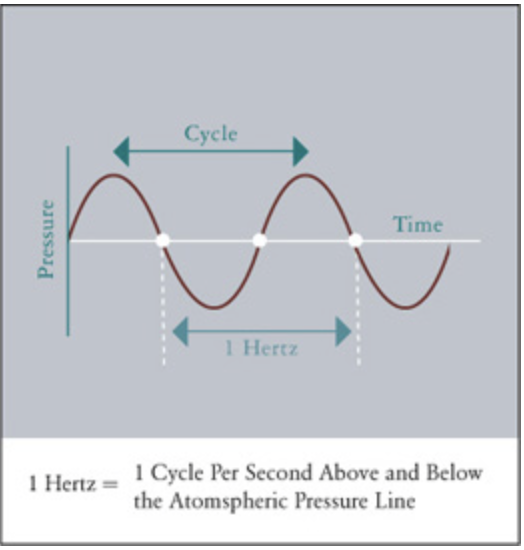

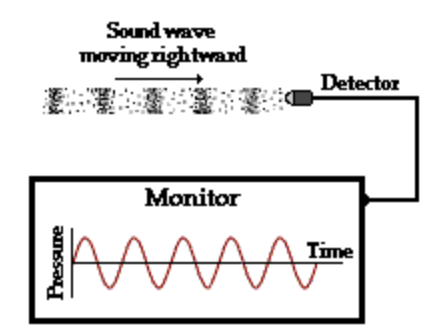

Here let’s say we have a speaker or a tuning fork on the left that vibrates back and forth (left and right). When the speaker moves right it pushes air molecules together, compressing them to create an area of high pressure. Then when the speaker moves back left there will be some space created that new particles can come and fill in. These will be areas of space with fewer particles and low pressure (rarefactions). We can measure the pressure of the air particles at every point in time and plot it to get a view of the sound wave created by the speaker.

Here let’s say we have a speaker or a tuning fork on the left that vibrates back and forth (left and right). When the speaker moves right it pushes air molecules together, compressing them to create an area of high pressure. Then when the speaker moves back left there will be some space created that new particles can come and fill in. These will be areas of space with fewer particles and low pressure (rarefactions). We can measure the pressure of the air particles at every point in time and plot it to get a view of the sound wave created by the speaker.

The frequency of a sound wave refers to the number of cycles/vibrations per unit of time. A single cycle/vibration is commonly measured as the distance from one compression (or rarefaction) to the next adjacent compression (rarefaction).

- The ear is sensitive to ratios of frequencies (pitches) rather than to differences in establishing musical intervals.

The fundamental frequency of a string is inversely proportional to its length, so vibrating longer strings, makes a lower note.

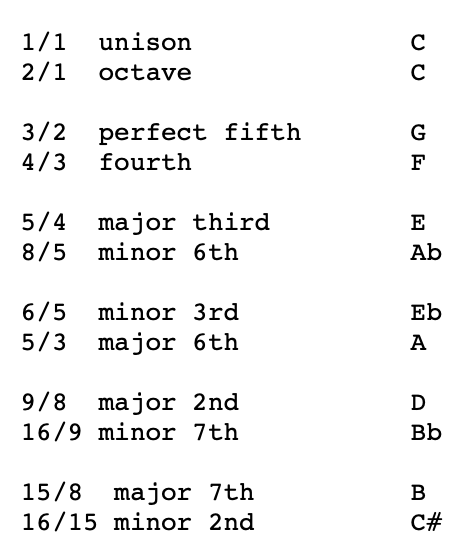

The Greeks realized that sounds which have frequencies in rational proportion are perceived as harmonius. Pythagoras, who experimented with a monochord, noticed that subdividing a vibrating string into rational proportions produces consonant (two tones are said to be consonant if their combination is pleasing to the ear, and dissonant if displeasing) sounds. Here’s a video of a monochord https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYtSI4-ShLU

Here are some ratios that sound good and their corresponding notes in the key of C.

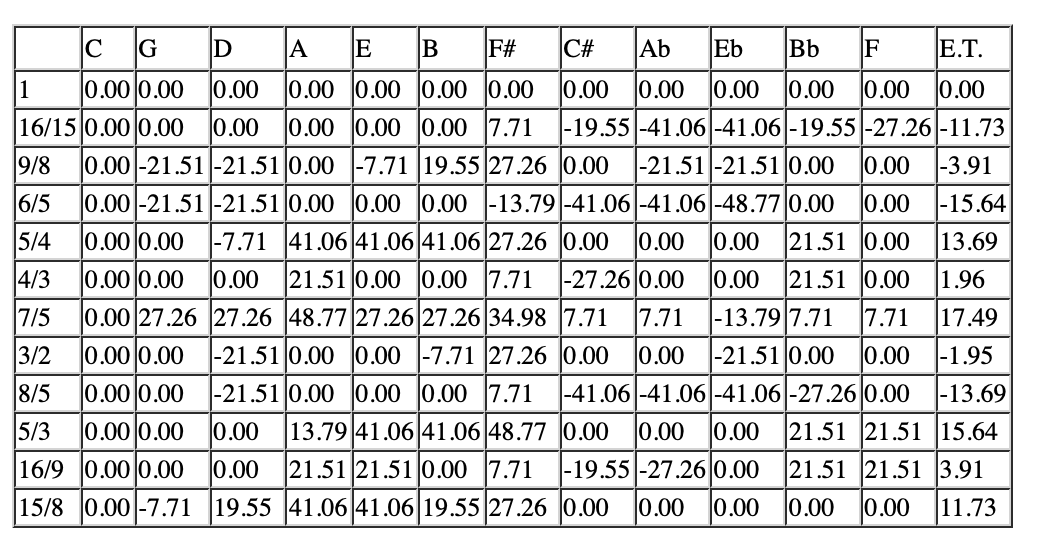

Suppose we just tuned our instrument to C. The following table depicts in cents (percentage of a semitone), how poorly a justly intoned piano tuned in the key of C would do in capturing the various intervals in the various keys. This is compared, in the last column, against equal temperament. For example, the table says, that in the key of A, a major third would be off by 41% of a semitone. Notice in the last column, that, while equal temperament captures the intervals 3/2, 9/8, 4/3, and 16/9 quite well, the other intervals are all off by more than 11% of a semitone.

In particular, if you don’t use equal temperament then different keys sound different.

An equal temperament is a musical temperament or tuning system, which approximates just intervals by dividing an octave (or other interval) into equal steps. This means the ratio of the frequencies of any adjacent pair of notes is the same, which gives an equal perceived step size as pitch is perceived roughly as the logarithm of frequency

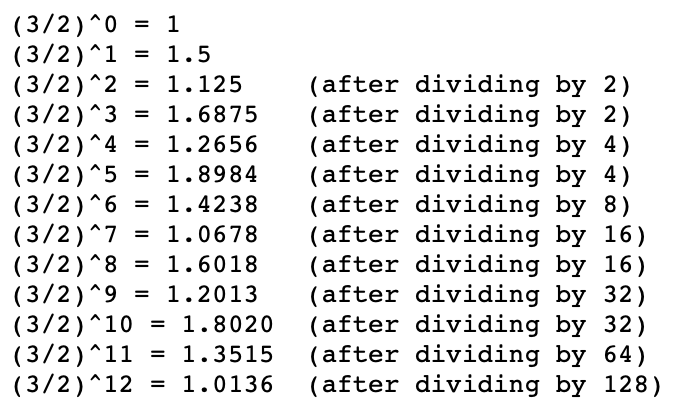

The idea behind twelve is to build up a collection of notes using just one ratio. The advantage to doing so is that it allows a uniformity that makes modulating between keys possible. Unfortunately, no one ratio will do the trick exactly. However, the ratio of 3/2 happens to work reasonably well using 12 steps. With 3/2 as the basis for the scale, none of the above ratios besides a unison, fifth, and major 2nd are captured exactly.

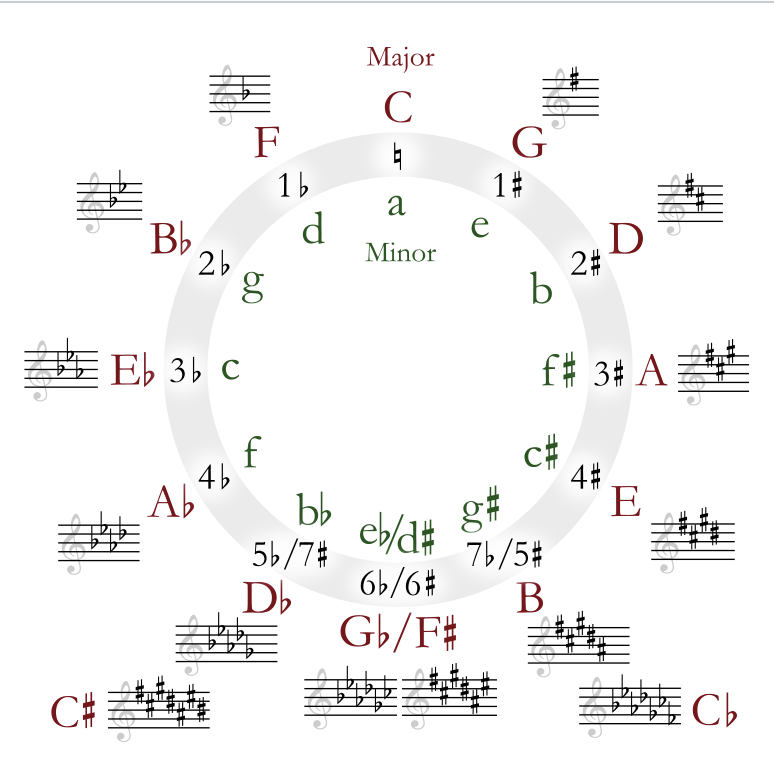

Here we have the circle of fifths:

However the most important constraint- namely that we get a repeating pattern going up in octaves, is almost satisfied by this scheme. Namely, after 12 applications of the ratios 3/2, we come back very close to where we started from (always dropping down by an octave, i.e. dividing by 2, each time the ratio exceeds 2):

- These 12 frequencies correspond to the circle of fifths. If we start from C, we then get G D A E B F# C# Ab Eb Bb F and back to C.

The choice of 3/2 says that, next to the octave, it should be regarded as the most important interval. So, we want to understand when a power of 3/2 will be close to a power of 2 so we can use 3/2 to approximate an octave: We solve the equation:

where .

We want to find a good fraction approximation for

And we happen to choosse the approximation 7/12 = .5833333333… which suggests using an octave of 12 steps, with a fifth equal to 7 semi-tones. Therefore, in equal temperament, a half-step is the same as a frequency ratio of ; that way, twelve half-steps makes up an octave. In the modern equal temperament (which came into practical use during the early part of the 20th century), all fifths are tuned to 2^(7/12)=1.49651…, slightly less than 3/2, and 12 repetitions of this ratio gets us back to where we started (after dropping down 7 octaves).

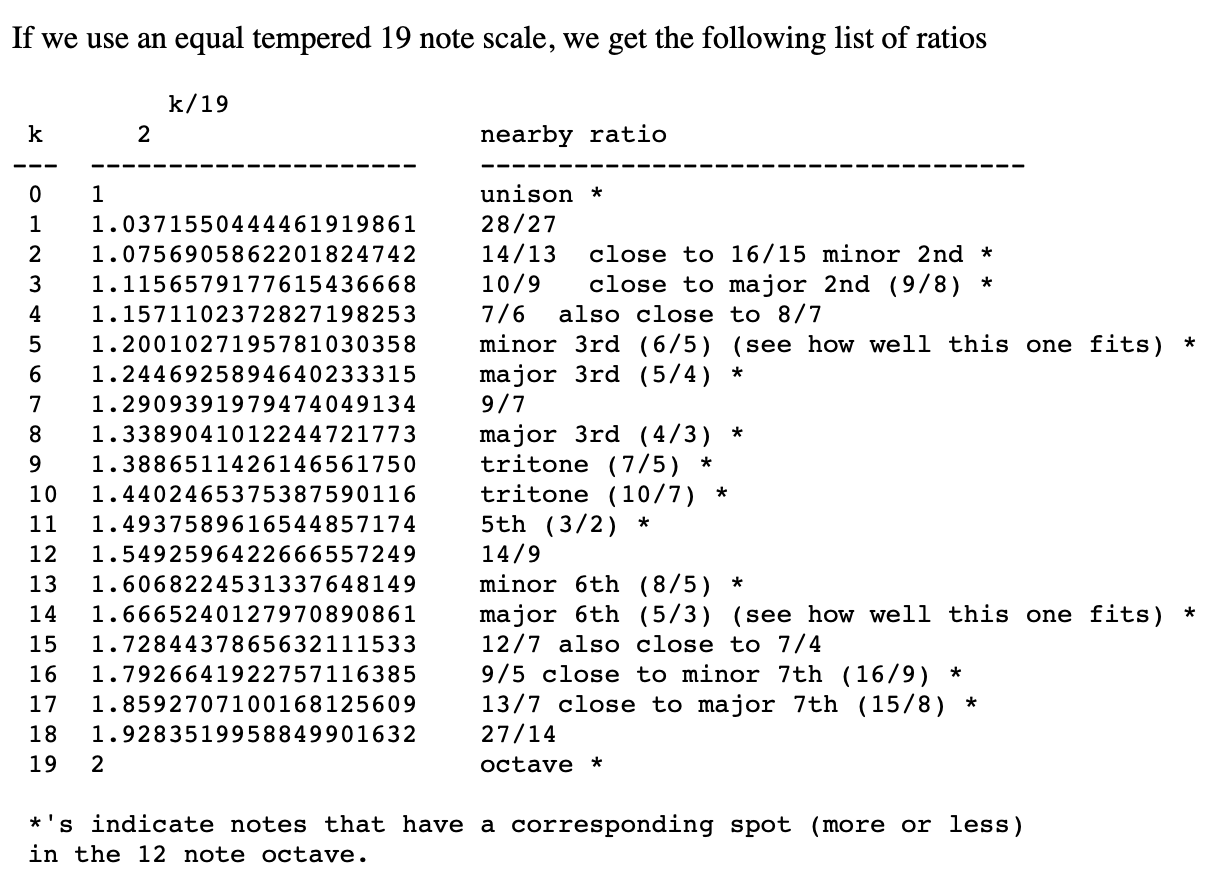

One can also use a major 3rd (i.e. ratio of 5/4) to build up a scale. If one, similarly, forms the continued fraction for log(5/4)/log(2)=.32192809…, one finds the following list of approximating fractions: 1/3, 9/28, 19/59, 47/146, etc. This suggests, for example, that a 28 note scale would work nicely using the major 3rd as the basis for its construction.

On the other hand, we need not always work with the best. For example, 11/19 = .5789… is reasonably close to log(3/2)/log(2) = .5849…, and 6/19 = .3157… is reasonably close to log(5/4)/log(2)=.3219…. This suggests that a 19 note scale with a major 3rd being 6 ‘semi-tones’ and a perfect 5th being 11 ‘semi-tones’ might work nicely. In fact, 19 appears in the denominators of rational approximations of the continued fractions for log(5/3)/log(2), and log(6/5)/log(2). This says that 19 would also work well for capturing the reciprocal pair of ratios 5/3 and 6/5.

The sharps and flats don’t really mean annything. The white keys are an “historical accident”, being the keys of the major scale of C.

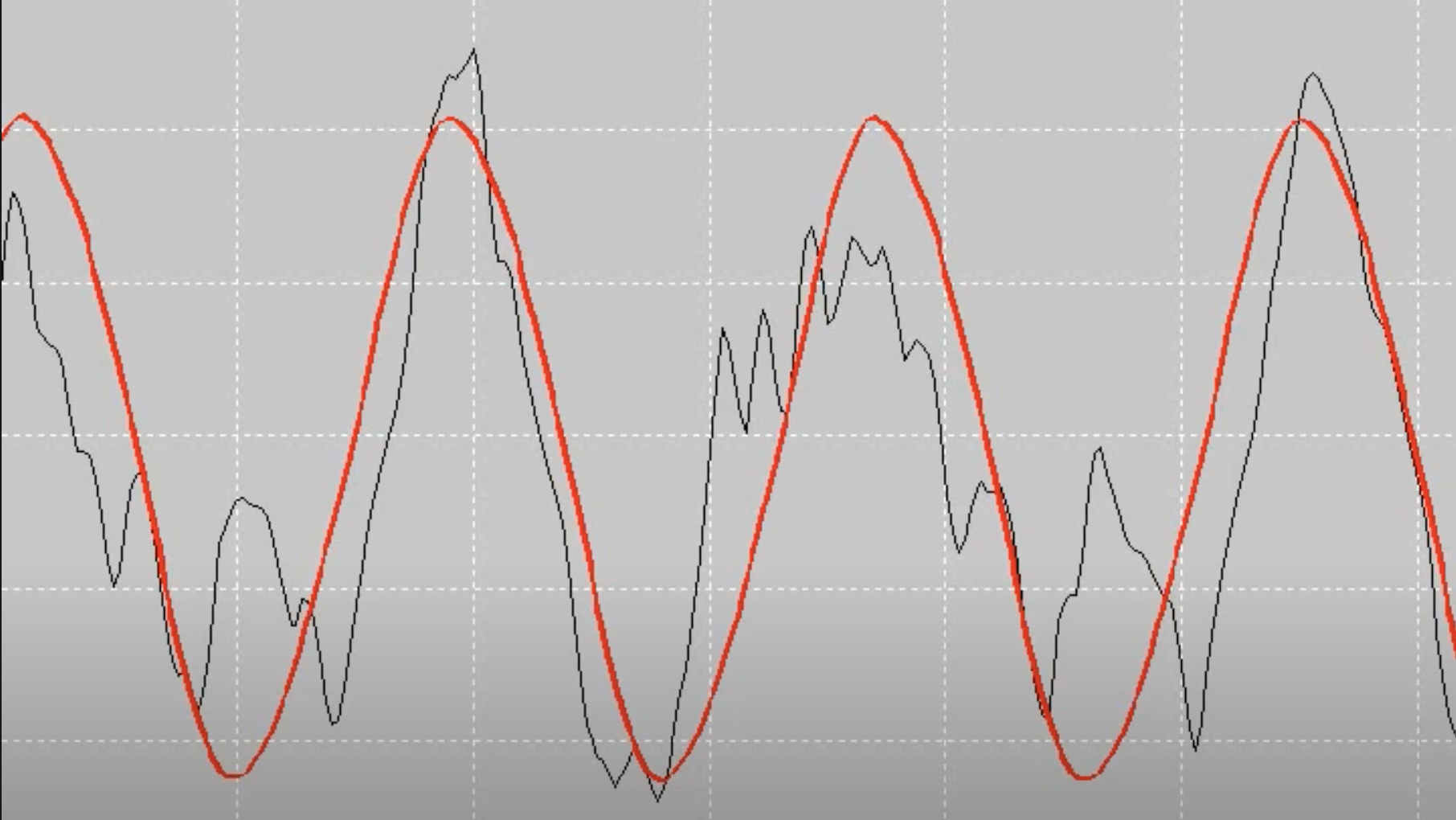

Here is the sound wave of an A at 100Hz produced elecontronically (red) overlayed with an A played by an acoustic piano (black). The red curve is only the fundamental frequency, which is why it looks like a perfect sine curve. The acoustic piano has harmonic frequencies that give it its unique sound (or timbre), which is why a piano sounds different from say a guitar even when they play the same notes.

A musical note is a harmonic series, or the sum of a bunch of different sin/cos waves. The lowest frequency member of the harmonic series is the fundamental frequency and the pitch of a note is usually perceived as the lowest as the fundamental frequency.

Any tone you produce in nature carries with it has a Fourier series: where the coefficients and determine the timbre of the sound. This is why different instruments sound different even when they play the same notes, and has to do with the physics of vibration. So any tone which you hear at frequency almost certainly also has components at frequency , , … etc. Because of the typical spacing of the resonances, these frequencies are mostly limited to integer multiples.

Notes mentioning this note

There are no notes linking to this note.